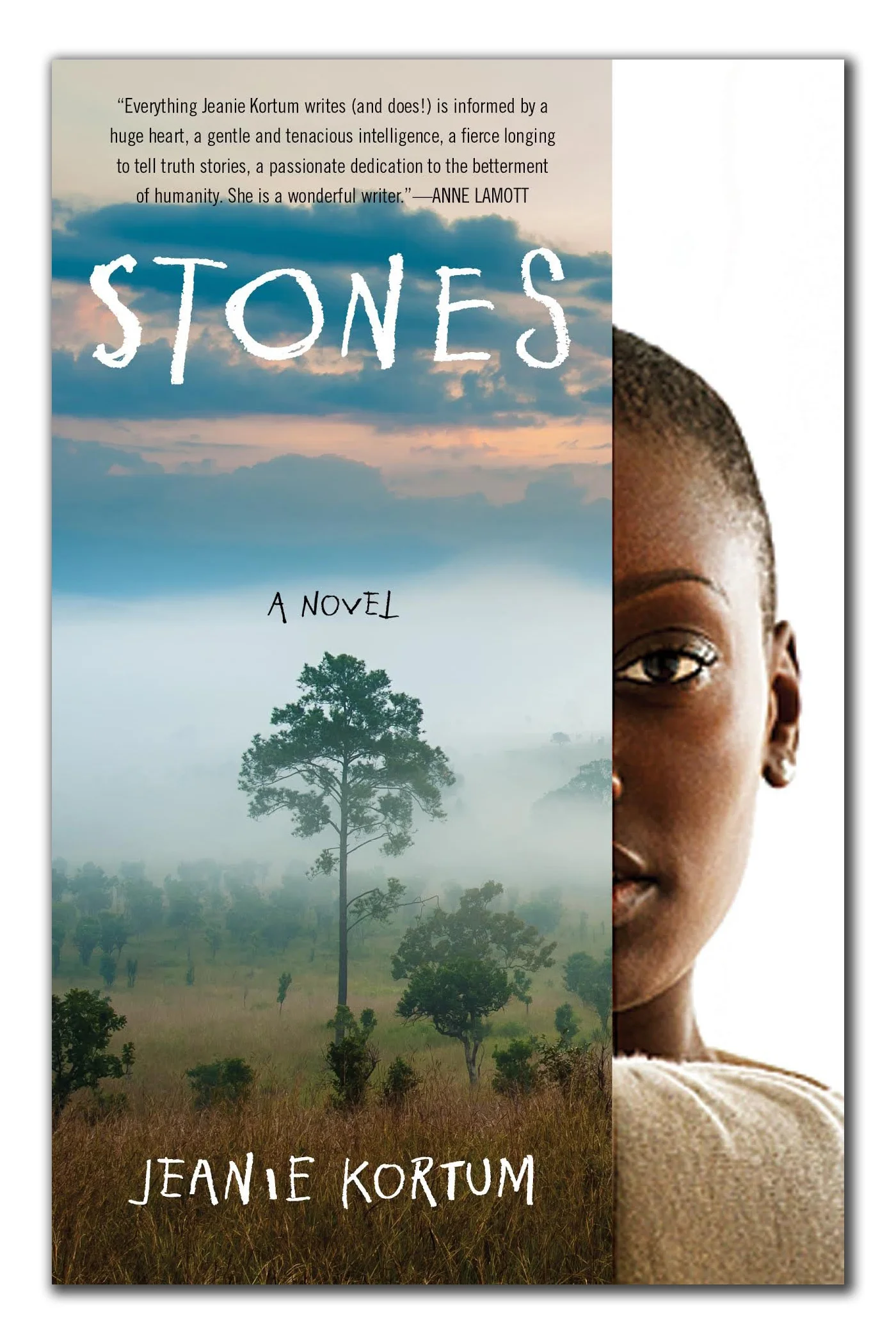

An Excerpt from Chapter 5 of Stones: A Novel

The last time you saw me alive, Granddaughter, you were only five. I was sliding up one side of my breath, trying to bring it in, falling down the other side, trying to push it out. And what were you doing? You were clinging to my neck, squeezing so hard I could barely breathe. And that wasn’t a good thing, because I needed all the air I could get for the matter at hand; I was dying.

“Don’t go, don’t go,” you called, only inches from my ear. No one had ever left you before. “Granddaughter,” I wanted to say, “can’t you see I’m a little busy?”

A hygienic swish of white robes, and Father Joseph entered the hut. What has my foolish, God-fearing daughter done now? Get that man out of here! The last thing I needed in all the world was a priest.

He glanced at me. “Looks like I’m here just in time,” he whispered. And my daughter? Well, she looked at Father Joseph like he was providence itself, everything I’d taught her chased out of her ears by church and that small-minded, bland husband she married. She didn’t even keep the name you were supposed to have, “Amely,” the name waiting for you chiseled on the walls of a cave deep in the forest. She changed your name to the more ordinary Emely. Never mind. You will always be Amely to me.

“I thought you could administer last rites,” my daughter said, wiping tears from her eyes.

Father Joseph walked over to my bed, looked down, and laid his hand on my forehead. “May the Lord in His love and mercy help you with the grace of His Holy Spirit,” he intoned.

Well, you, Amely, you weren’t having any of this, were you now? You pushed under the priest’s arm, climbed up into my bed, pressed your hot little body against mine. If I’d had more energy, I would have laughed.

The priest put his hand on your shoulder. “Emely,” he said, “give your grandmother a little more room.”

Room. Ha! Shows how much he knew about dying! The last thing in the world I needed was more room. What I needed to do was to try to get small, because I was headed toward that point of light out there. I had to get so small I could slip through it. And that was a difficult assignment, because what I was discovering in those last few moments of my life was that the bodily house is full of light, that there was a constant movement against all the surfaces of who I was. Big light, huge light, and it was just as solid as my bones.

Just a few hours earlier I had somehow managed to rise from that bed. I’d had one last thing to do. I knew I was fast becoming a “was,” but I needed to stay an “is” a little bit longer. I’d moved slowly toward the garden, my pain filling the hut. “Amely,” I had called. “I have something to give you beyond the ears of your mother.”

In the garden, you climbed up into my lap, just as you always did, and I wrapped my arms around you. I knew I was giving you a burden—the burden to remember. The story I was going to tell you was the most holy story of all, but I needed to fortify you for the years away from me. You had the spaces inside for what the world was trying to forget. Even at the age of five, you possessed a steadfast purpose that chastened anything superfluous in your path. Everything alive was your family. Five or six dogs followed you everywhere. Everyone in the village thought you fed them, but that wasn’t it, was it? Somehow those animals knew you were their home.

Holes, more light. I was fast turning to lace. I had to tell this story quickly. “The ways of Jesus are fast spreading across this land,” I began that day in the garden. “They are erasing the old ways. Even your own mother doesn’t believe. But the story I will tell you goes back to a time even before Jesus was born. It goes back to the first fire. You must not be careless with it, though; this story belongs to many. It’s not just yours to give away.”

I was wearing my favorite old brown sweater. You stuck your fingers into its holes, hooking yourself into me. Somehow, you knew this story needed all ten fingers.

“There will be a time when you will use this story to save your life,” I continued, “and the lives of others. Do you promise to be careful with it, granddaughter?”

You looked up into my face, your eyes dark and serious. “Yes, Grandmama,” you solemnly promised.

If I weren’t dying already, the lie you told me that morning in the garden would surely have killed me right then and there.

I told you the story then, trying to tell it so well you would always have its melody to lean against. When I finished, you were quiet. “Where are you going, Grandmama?” you eventually asked. I remember looking down into your sweet face. The light behind me shone through me, and I saw some of that distance in your eyes as well.

“Far, far away,” I replied, trying to soothe you. “But close enough so that I will always see you.”

For the last time that afternoon, we sat together in the garden, and I said good-bye to everything I loved: plowing with my favorite ox, all the animal’s improbable and miscellaneous parts moving together across the red loamed earth; cooking chapatis over my fire (how many had I made in my life, circling, circling always, crimping the edges of the dough with my fingers, making that small wheel that spun my days forward toward this, my final moment?). I remembered as well the many times I had walked to the river, the soles of my feet burning with all that inhaled sun; the talk of the women running into the water, coming back as song; the dimpled bottoms of my grandchildren spilling over my arms. I remembered taking an ax to a tree for firewood, the split-open, just-been-born smell of it all; going to the fields for maize, the dry shiver of all those unclothed sheaths, the plump sweetness waiting inside; pounding the maize at the grinder, powder leaking down . . . this village, its noisy storms, its green pastures spilling toward the sky; love given back, really.

But most of all, Amely, what I hated about dying was leaving you. You were and are my best thing. Always, my best thing.

And now, a few hours later, I was back in bed doing the hard work of dying.

Father Joseph reached down into his robe and drew out a small, green velvet bag. “May the Lord turn His countenance to you and grant you peace,” he said in his important sermon-giving voice. He pulled the tassels of the bag and took out a silver cross and a small bottle. “Christ is the only true God,” he said as he unscrewed the bottle. “May this pagan heart accept Him tonight.” He splattered me with holy water.

Another voice began to hum in my ear. I am waiting for you at the edge of light. Friday, September, April? You say your tiny words, mount the tiny hills of your days, and none of this matters. I love perfectly, because I love nothing in particular. Words like lungsful of air, words that glowed in the dark. The Great Mother, the hard stone of prayer inside the blue, blue sweep of her sky.

No more pain now, I was traveling toward her, into her, becoming her. I could barely hear Father Joseph now.

Actual death is a little like floating. Loosened from the strange and wonderful grip of mortality, my body was changing. I was becoming pure movement, flowing into the curve of the sky. Women out there, many women, pulling me toward them—a hand, breasts, more hands, smiles . . . oh, such welcoming goodness! I was moving toward them, but before I was with them all the way, I turned one more time to look at you.

You knew I was leaving. Your eyes were large, and I could see that you’d reached down into yourself, to the place where you really live. And then what did you do? You leaned over the emptying husk that was my body and tried to give me your five-year-old breath. Your lips were warm and slightly damp against mine. I didn’t take that breath, and that’s how you knew I was dying—I had never refused anything from you. And that’s also when you pressed your body even tighter against mine. Even the priest and my daughter knew now to stay away.

Climbing, climbing, I was moving away from my final stillness, riding my last singular breath far away from the deep green of my home, toward and into the great indestructible Mother. I was small now, small enough to get through that single radiant point of grace out there. One last look back, and that’s how I know that in that final moment, you leaned over and pulled my last breath into you.

Mama, daughter, grandmama, the slide of those small syllables no longer fit; you don’t name one breeze in the wind, one wave in the ocean, do you? Africa, Okino, I belong to so many now, I am no longer just one name. There is no separation when you’re dead—no black, no white, no otherness. We all just run into each other, swirled together into one thick, rich consciousness. What someone knows in America flows into what someone else knows from Tibet. All experiences run into each other, too; lawyers, teachers, plumbers, doctors, and chefs—we have all sung our children to sleep.

And what we know is this: you’re in trouble, Amely, and we, the dead, watch.